Dear Readers! With Christmas around the corner, I wanted to gift you a chapter from The Story of Art Without Men – available at all good bookshops, across the globe in the UK, USA, France, Germany, Spain, Italy (more to come in 2024), and on Audible.

To get you in the mood, here’s a section from one of my favourite chapters: Weaving New Traditions, about the pioneering women who transformed textiles into materials of resistance, with their artistic and feminist magic. Enjoy!

Artists have been working with textiles for hundreds, if not thousands, of years: for function (clothes, blankets and even sound-proofing devices); as political tools (such as the banners made by the Suffragettes); for the purposes of storytelling and communication; or as a medium for self-expression. Using natural and synthetic fibres, ancient techniques and modern ones – stitching, quilting and weaving, bundling together old clothing or using found objects – artists have configured wall-hangings, three-dimensional sculptures, and giant, immersive installations.

Despite the innovative and progressive ways through which the medium has been handled, particularly in the twentieth century, textiles and embroidery have historically been derogated as ‘decorative arts’ due to their association with women. In feminist art-historian Rozsika Parker’s book The Subversive Stitch, published 1984, she writes about how embroidery was ‘characterised as mindless, decorative, and delicate’. But what the medium actually reveals is a deep political subtext, one that charts the history of oppression of women throughout the last 500 years.

First relegated from the high arts in the Renaissance, the lowly status of textiles was cemented by artistic academies in the eighteenth century (the Royal Academy of Arts in London banned embroidery within eighteen months of its opening). This meant that women had to actively reject the medium if they wanted to be taken seriously. Even in the twentieth century, schools such as the Bauhaus, which sought to diminish hierarchies between art forms, revealed its gender and form hierarchy by sending women off to the weaving workshop. And if you need any more convincing that it was Western patriarchal ideals that forced these associations slowly into existence, it might come as no surprise that Le Corbusier was once quoted as saying: ‘There is a hierarchy in the arts: decorative art at the bottom, and human forms at the top. Because we are men.’ No wonder artists in the 1970s feminist movement used the needle as a form of protest.

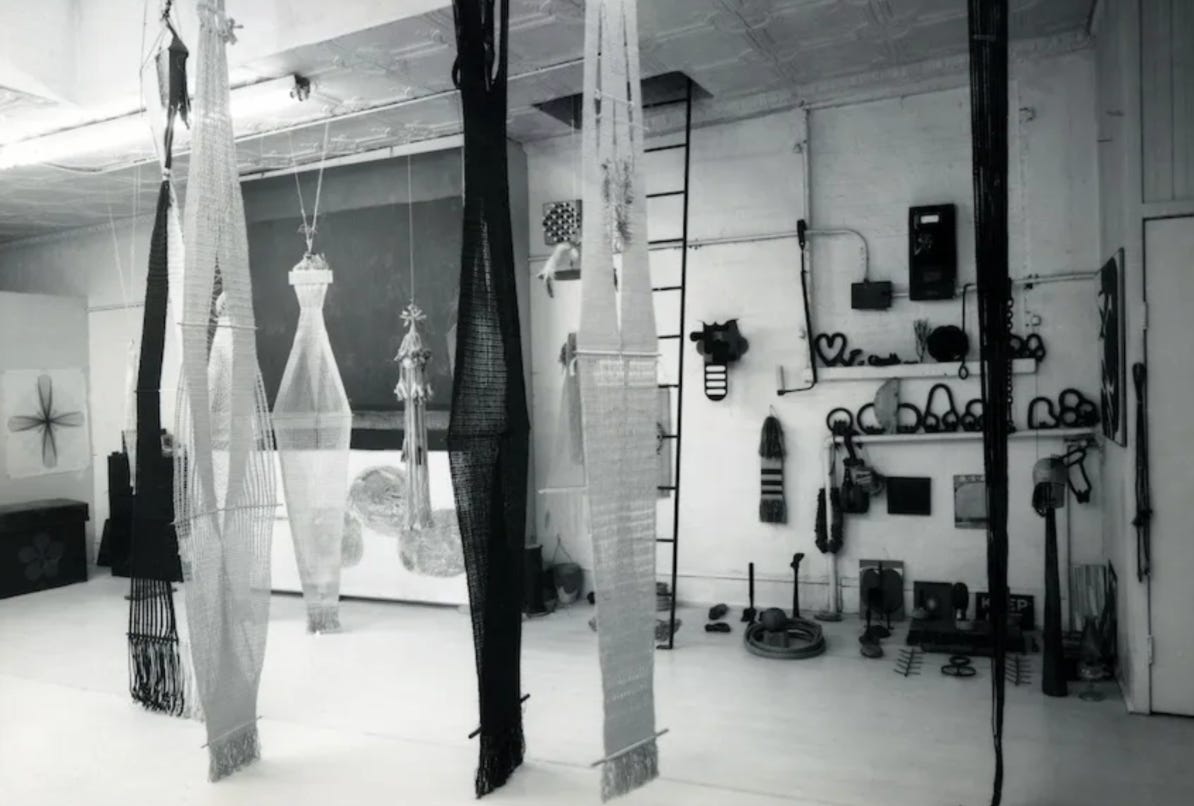

Alongside feminist art, things changed. When artists expanded the supposed limits of weaving in an advanced and improvisatory way, adopting both ancient techniques and working ‘off-loom’, institutions began to take note of the emergence of ‘Fibre Art’. Landmark moments included Wall Hangings at MoMA in 1969, outlined by the museum as the first group exhibition in America ‘devoted to the contemporary artistic weaver’.

Looking at new ways of approaching the medium in the realm of fine art, the show featured Lenore Tawney (1907–2007), a former New Bauhaus student, and her highly inventive ‘woven forms’ inspired by Peruvian techniques. Also included was Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930–2017), who used woven fibre for her vast-in-scale, malleable bodily forms (which she called Abakans). Responding to European tapestry traditions, Abakanowicz pushed forward new ways of thinking about textiles as installations and encouraged 360-degree looking. Exhibited alongside these artists was work by a young Sheila Hicks, who was fresh out of Yale having been taught by Josef Albers (and briefly, informally, by Anni Albers).

While artists working in textiles feature throughout this book, I want to use this chapter to draw a distinction between them and those just mentioned who exclusively used textiles as their medium. I have chosen to do this here to highlight the range of experimentation, and before we discuss the Women’s Liberation Movement. This is also the only chapter that spans numerous decades, as fibre is an artform that is steeped in history.

We begin with Hicks, who emerged in the 1960s with the Fibre Arts Movement, and end with quiltmakers, who continue to practise century-long traditions today. Although some of the artists I will discuss were working at the same time as the feminist movement, which saw women embrace the domestic forms of textiles, their art has a less overtly political agenda and stems from different traditions. From sculptors, weavers and quiltmakers, to the self-taught and neurodiverse, for me, these artists broke ground with their rad- ical works in fibre, despite so often being dismissed by establishment.

Oozing with bright colours, glittering surfaces, rich textures and organic, at times cosmic, forms, looking at work by Sheila Hicks (born 1934) tends to immediately provoke intrigue and astonishment. Whether it is her smaller weavings inspired by pre-Columbian textiles learned in her youth while travelling in Latin America (which she calls ‘minimes’) or her colossal architectural environments that pour out of ceilings or swarm entire rooms – a more recent example being Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands, 2016–17, Hicks’s fibre creations break down all tensions between art object and viewer. By encouraging us to sit down, reflect, and physically feel and touch her artworks, she creates environments where we can be at one with her work. For her, tactility is key.

The same can be said for Chilean-born poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña (born 1948), who, like Hicks, has been active since the 1960s and works on an all-encompassing scale that disrupts all perspective and engulfs us as viewers. Cascading from the ceiling in a formation of forest-like abundance, Vicuña’s fibre works incorporate the Indigenous traditions of quipis – a system of communication relying solely on hand-tied knots used by the Quechua people. One can get completely lost in her immersive installations, which invite us to participate as performers as well as engage in a wider language that doesn’t necessarily need to involve speech.

Working quite apart from the Western art world, the Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee (1924–2015) configured the most extraordinary sculptures from dyed rope (either hung from the ceiling or standing by themselves). Working purely intuitively, without sketches or preparatory work, and drawing from folk art, nature and mythology, Mukherjee employed a hand-knotting technique (known as ‘macramé ’) for her towering, regal figures. Full of expression and animation, when witnessed in real life they come alive and command power, and when exhibited together they appear like ancient deities who once ruled the world. Looming over us (at times nearly double our height), in forest greens, burnt oranges and rich, deep purples, Mukherjee’s figures feel both human and otherworldly, protective and monstrous, as they oscillate between abstraction and figuration in their labour-intensive, elegant, thick and thin folds.

In America, the self-taught Judith Scott (1943–2005) was using fibre in a completely different way. Her fluid and complex sculptures merge wheels, trolleys, locks and chairs with bundles of threads – some of these pieces she would work on for six hours straight, or months at a time. While Scott has often been positioned alongside those in ‘Art Beyond the Mainstream’, I believe she deserves to be placed among the greatest innovators of fibre. Her inventive methods and obsessively spun sculptures cocoon found objects and function as a form of communication – which is particularly extraordinary for someone who couldn’t hear or speak verbally.

Born with Down’s syndrome and an undiagnosed deafness, from the age of seven Scott’s family placed her in a series of mental institutions. She endured horrific conditions for more than thirty-five years, until 1985, when her twin sister, Joyce, born without disabilities, became her legal guardian and brought her to California. Here, Joyce enrolled Scott at the Creative Growth Art Centre in Oakland, one of the first places to provide artistic freedom for people with psychological or physical disabilities. She made nothing for the first two years of her time there, but after participating in a fibre art workshop Scott became obsessed with threads. She spent the next seventeen years of her life (until her death, aged sixty-one) fastidiously wrapping, bundling and spinning fibres around objects, transforming them into her extraordinary creations, such as in Untitled, 2004, which buries a chair, a bike wheel, a basket and more, under layers of an assortment of kaleidoscopically coloured fibres.

Like those working with fibre, quilters have also mainly been left out of art-historical scholarship, even though the medium has been a staple of textile art for centuries (as seen in the work of Harriet Powers, working in the 1890s, image above). Through quilts, artists have expressed political and cultural viewpoints, recited stories or just continued age-old traditions through a long line of female family members.

Whether you're an art history aficionado or simply curious to explore the great contributions of women artists, check out The Story of Art Without Men, available in US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain + on Audible. Happy Christmas! Love Katy Xoxo.

Thank you Katy for your fun book I bought just after its release.

I went to Art school in Edmonton, Canada beside a Fibre Artists class, a three year study program, and all you can imagine

with weaving on huge computerized looms to tiny knotting and knitting. I would run down to their Art rooms every chance I had to see what they were spinning that day. One day a indigenous Artist asked me if I would help her wrap a TiPi in

burlap, that she’d washed and buried in the soil and then washed and buried again! After this taking place for many sessions,

I couldn’t help smile as I lifted the softest fabric I had ever touched, and we wrapped the wooden poles to the very top. She set up an altar for prayers to her grandfather inside the soft light.

Wonderful to read this chapter on fiber artists. Mrinalini Mukherjee's work especially speaks to me, as she gives permanent form to presences that are live unseen among us.