I want to tell you a story I first heard late last year. It was a dark afternoon in November, and I was at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. On view, was an exhibition about families. It looked at how varied and complex families can be, and how they shape our society and relationships, too. Curated by Susan Golombok, a family psychologist, it featured works that explored love, loss, motherhood and step-motherhood; families from history and families now.

It was full of paintings, photographs, sculptures and installations, both large and small. But it was a few faintly-applied drawings, by Mary Husted, from 1962, that caught my eye.

In 1962, Mary Husted was 17-years-old. She had become pregnant, but, as an unmarried middle-class woman, this wasn’t socially acceptable. To see out (and hide) her pregnancy – and avoid the supposed shame and loss of reputation – she was sent away by her family, and forced to give up her child for adoption at birth.

“At no point was I ever told of any way that I might be able to provide for myself and a child,” she later said in a statement to the Human Rights Commission.

Husted travelled to Reading to live with a family friend, although her family told people it was Germany. No doubt isolated and scared, Husted gave birth to a baby boy on a cold, late January morning. She called him Luke. They were allowed 10 days together.

How do you capture enough love for your newborn that will last you a lifetime? Or retain the memory of how you saw them, or how they made you feel?

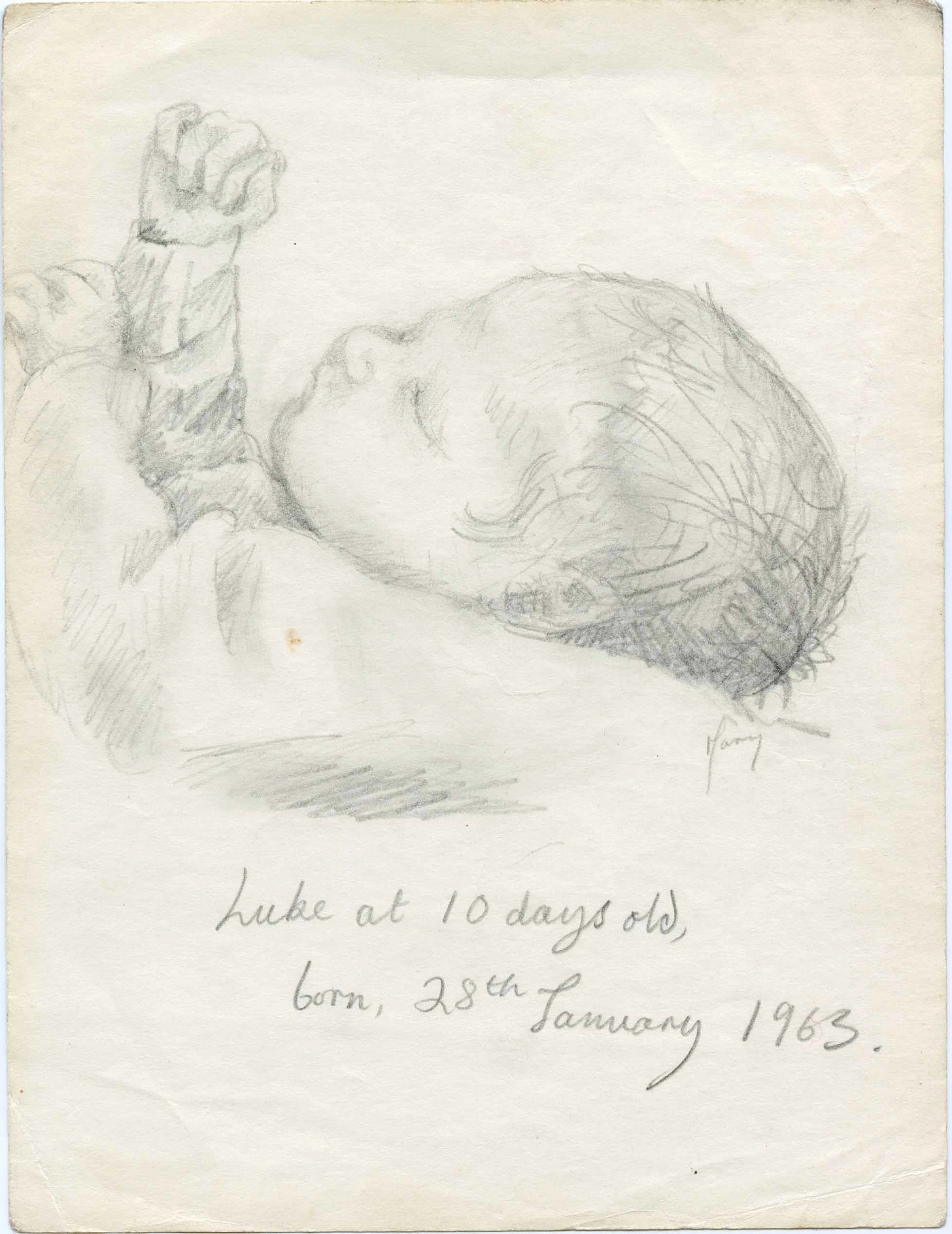

Husted didn’t have a camera, so she sketched her baby, analysing, in soft pencil marks, every hair, eyelash, and wisp of his brow; how he clenched his hand, how he slept, the delicacy of his face and the way his head imprinted onto his pillow.

You can tell that she’s trying to retain this feeling forever. As she said: “I had to draw those because I knew I’d forget a lot of them.”

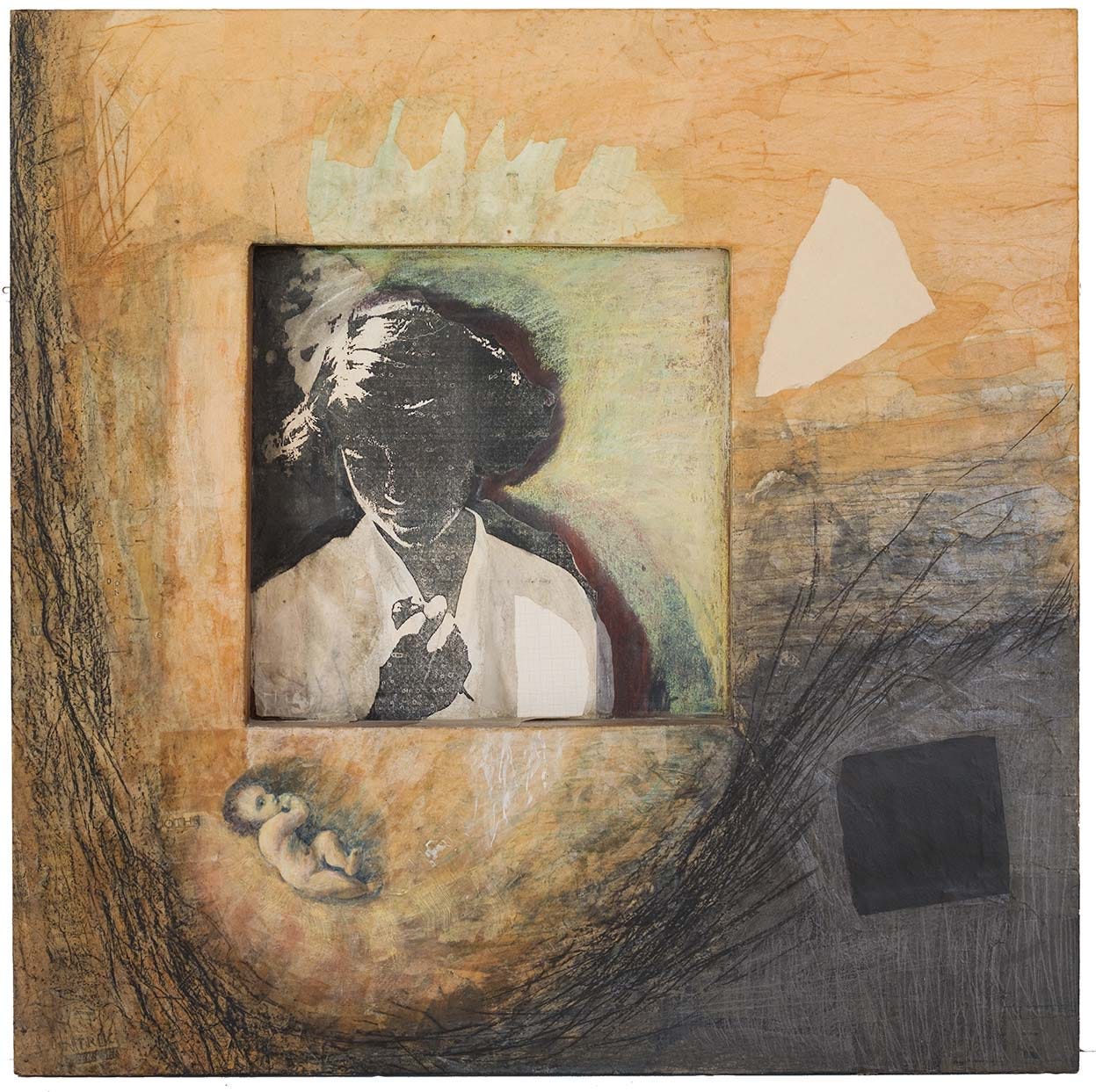

Husted kept her drawings close, and a few years later began a family of her own. She had three children with one husband, and another with a second. But it was only after her fourth child left home that she returned to art. She always remembered baby Luke, and – wondering where he might be now, what kind of childhood he would’ve had, and the mother she might have become – reflected on this in a painting she called Dreams, Oracles, Icons, in 1991. She used her sketches as inspiration.

The result was a golden collage (it was also in the exhibition), with a newborn in the foetal position in a nest-like form at the bottom. In the middle, a separate square plane, that pictures a contemplative print of a mother mother tightly holding a bird, perhaps setting it free.

To me, it’s a portrait of love, longing, and love lost.

Soon after she made this, it entered the Women’s Art Collection at Murray Edwards College, Cambridge University (home to the largest collection of art by women in Europe, and where I am lucky enough to be an Honorary Fellow). Although Husted wasn’t keen to give it away (it was her most meaningful piece), she eventually agreed. It would be for the public, for other mothers who might relate to her situation, and, who knows, “out there if he [Luke] was ever looking for me”.

Decades later, in 2007, baby Luke was now 44. He was married with two sons, and looking for his mother.

Thanks to changes in adoption laws, he was able to track down her name, and, in the age of the internet, searched “Mary Husted”. Alongside her name was Dreams, Oracles, Icons, with the pencil-marked memory of him as a baby in a nest-like form, on the College’s website. He found her email, and, a couple of weeks later, they met, and – thanks to her drawings and paintings of love – have now been in daily contact ever since.

I recently asked Husted if she ever envisaged that these small drawings might become significant in the way they have. She replied:

“No. They were at the time for me and me only. Nothing I had drawn or painted in my one previous year of art study was any good, but these drawings were. I did not know that then, but I see it now. Need and yearning drove them. They were all I would have of him. It may sound trite, but I would say that love made those searching, tentative lines on the paper. That’s where the power came from.”

One of the most moving stories in art history – it was seeing these drawings and painting that made me realise the many powers of art: how it can provide memories that last a lifetime, make people feel seen and less alone, and, ultimately, bring people together.

Thank you for reading this Substack. If you think someone else might enjoy this too, please spread the word. If you have any feedback, please comment below.

Love, Katy.

Thank you for this beautiful story. It has reminded me of something so essential—that the power of love, in art surpasses technical skill; when called upon in our work it manifests a power, a mystery, that transcends the analytical mind and transforms us. This is the unique gift of the woman as artist, because her depth of emotion connects her body to love in an alchemical and biological manner.

Mary Husted… the plight of many women, this envelope of love and yearning shown in the art and separation is heartening.