Hello readers,

To celebrate this Thursday’s paperback release of The Story of Art without Men (ft. a new cover and bonus chapter), I thought I’d share with you a section from one of my favourite chapters: Abstract Expressionism.

While the movement included, among others, Lee Krasner and Helen Frankenthaler, here, I want to spotlight the great Joan Mitchell.

Listen to the chapter for free via The Great Women Artists Podcast.

Enjoy! Katy Xoxo

“Painting is the only art form except still photography which is without time. Music takes time to listen to and ends, writing takes time and ends, movies end, ideas and even sculpture takes time. Painting does not. It never ends, it is the only thing that is both continuous and still. Then I can be very happy. It’s a still place. It’s like one world, one image.” – Joan Mitchell, 1986.

Ambitious, bold, energetic; full of action, scale, intensity, drama, Abstract Expressionism – a term loosely applied to artists working in New York in the 1940s and reaching their zenith in the 1950s – marked the entry point to America’s abstract avant-garde: a movement that paved the way for radical art-making in the latter half of the twentieth century.

With some artists making sweeping, gestural marks, and others extravagantly applying paint to create strokes that glide across the canvas or are poured, sculpted or slashed, the artists associated with the movement carved out an entirely new abstract language.

Artists from one school of the abstractionists (sometimes called the action painters) were bound up in dynamic, gestural painting. Their style pointed towards the excitement of a new world, but also reflected the realities and their personal experiences of the Great Depression, the Second World War and the atomic threat that felt ever closer in the Cold War era. Turning to new tools and materials – from household enamel paints to the recently invented acrylic paints – they used decorators’ brushes and palette knives to create striking, jagged textures.

Many of these artists working in New York, male and female alike, studied, exhibited and socialised together – from drinking at the Downtown Cedar Tavern (where, in the words of artist Lee Krasner, ‘the women were treated like cattle ’) to showing in the famous 1951 Ninth Street Show (the defining exhibition which brought together the different generations of Abstract Expressionists).

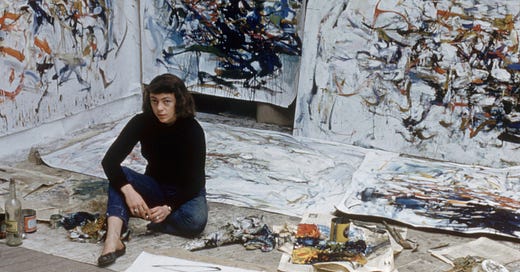

Making her New York debut at the Ninth Street Show, Joan Mitchell (1925–92) stood out as one of the leading artists of the day, with her tough, fleshy, gestural painting. A frequenter of the hard-drinking Cedar Tavern, an avid smoker and famed for her feisty personality (in 2002 The New Yorker described how ‘a wry set to her mouth would portend the utterance of something startlingly smart and, as often as not, scathing’), Mitchell was a genius at transforming paint into gusts of light, energy and movement.

Applying her oils with strokes that varied from feathery and translucent to thick and aggressive, she would squeeze out entire tubes or vigorously throw paint onto the canvas. Unlike her contemporaries, Mitchell looked to the French Impressionists for influence, creating a vernacular that expanded on late-nineteenth-century painting.

Born in Chicago to a wealthy family, Mitchell’s youth was spent amid the city’s cultural elite; her mother was a poet and her father a doctor. Her childhood wasn’t straightforward, though, as she had a complex and abusive relationship with her father, who wished she had been born a boy. Competing (and succeeding) in figure-skating, horseback-riding and diving competitions in childhood, by her early teens, Mitchell had already decided she wanted to be an artist.

Financially supported by her family, she studied in Chicago, spent summers painting in Mexico and then a year in France, before settling in New York in 1949. Quickly immersing herself in the art scene, Mitchell was also close to many of the era’s great poets – from Frank O’Hara to James Schuyler – and exhibited at the famous Stable Gallery. Within nine years of her arrival, her work Hemlock, 1956, would be acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Mitchell’s compositions made in the first half of the 1950s feel, to me, intensely compact and claustrophobic, then as the decades progressed (following her regular travels to France from 1955 and permanent move there in 1959), they transform into looser, freer works.

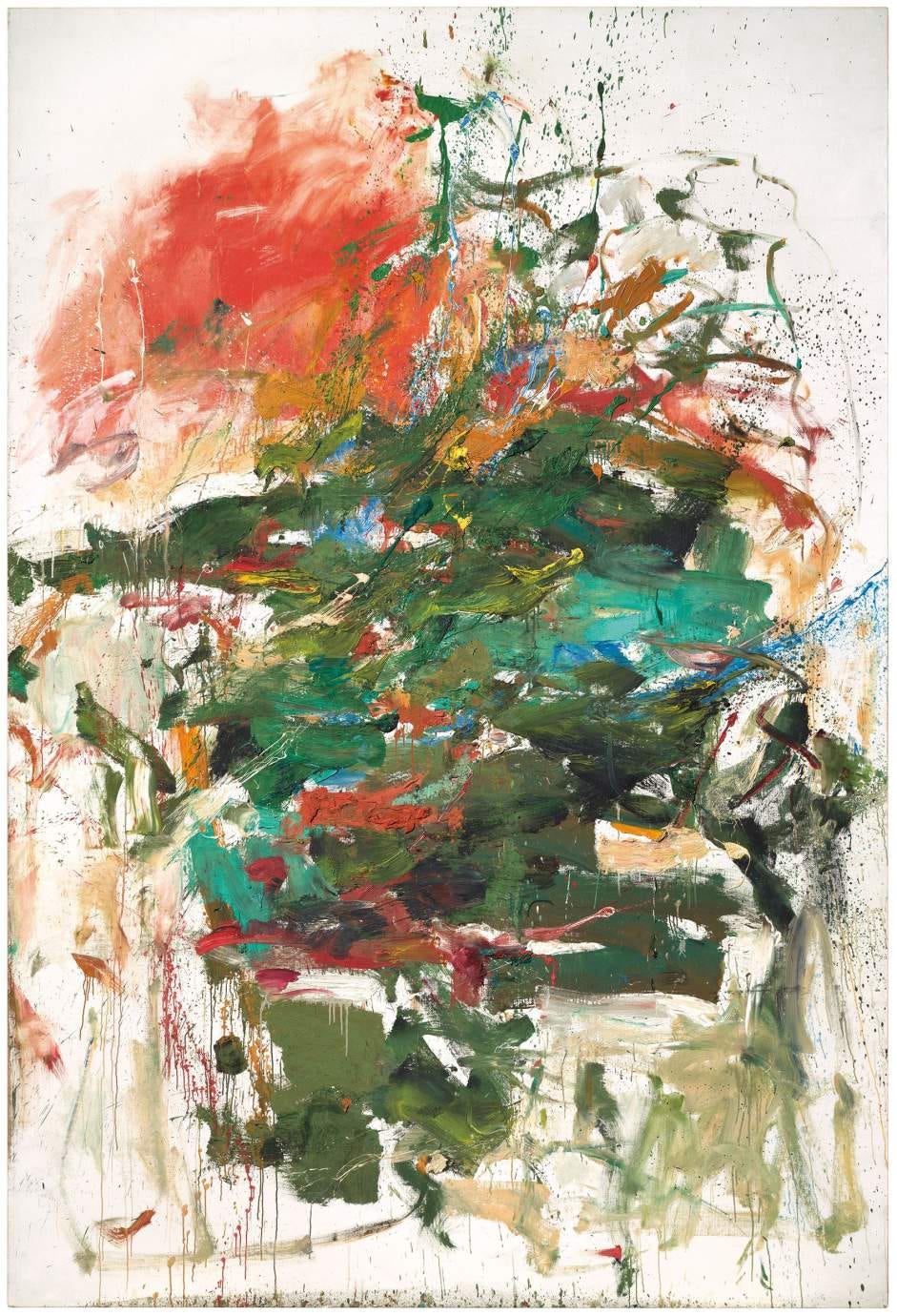

A spectacular example of this is 12 Hawks at 3 O’Clock, c.1962. Smacking and smearing layers of paint onto the surface, it is as though she is conjuring (or tearing apart) centuries’ worth of painting in her tough, gritty, yet dazzling-toned canvases. Like Krasner’s Night Journeys series, you can almost imagine her fighting the work with industrial, heavyweight brushes, the vigour of her gesture exuding her determined character.

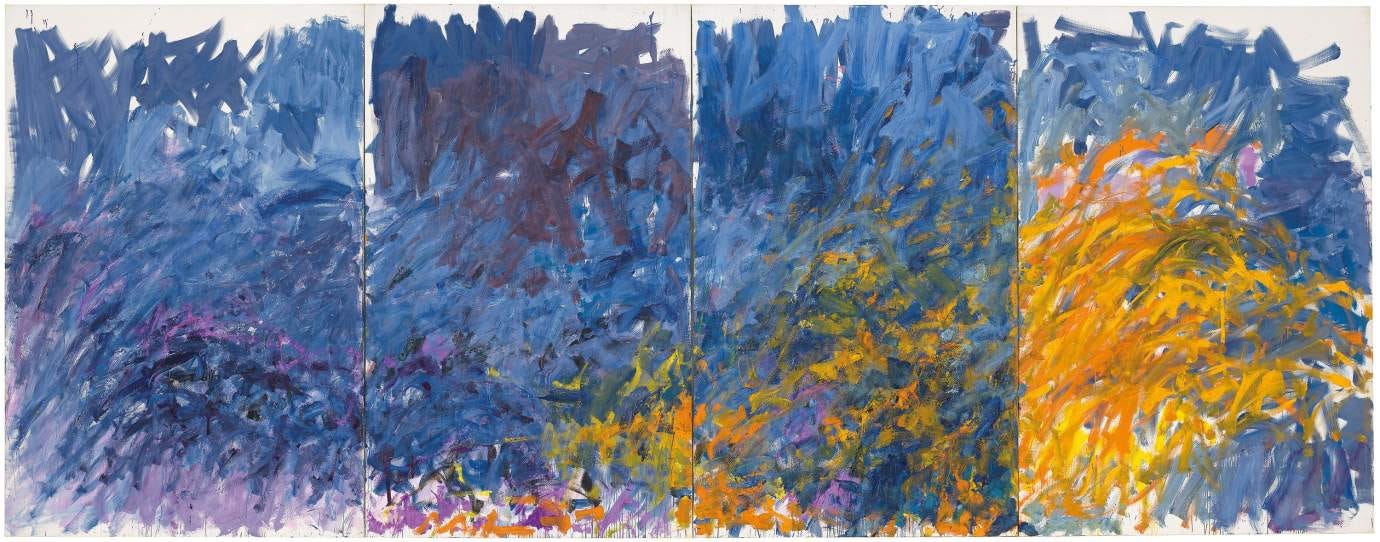

Drawing from the colours of nature, and often referencing the aesthetic of Monet’s Water Lilies, Mitchell’s later works verge on the sublime. This is especially evident in her four-panelled Edrita Fried, 1981, which at nearly eight metres long radiates a fiery energy and a dancing luminosity through the rough tides of scrubbed indigo that attempt to overcome the flame-like ochres.

That’s it from me! Happy GWA’ing. Thank you for reading this Substack. If you think someone else might enjoy this too, please spread the word. If you have any feedback, please comment below. Love, Katy.

Fascinating

Thank you forming a venue encompassing work of fantastic girls !